The Economics of Bitcoin Block Size

Bitcoin as a currency has proven its worth in last 8 years. It has the properties of ease of transfer, fungibility, divisibility, scarcity, and durability -which are missing in traditional fiat currencies as well as gold. However, it faces constant challenges from traditional payment systems, primarily regarding the maximum throughput of transactions per second (currently ranging from 3–7 transactions/sec as compared to Visa which averages 2000 transactions/sec).

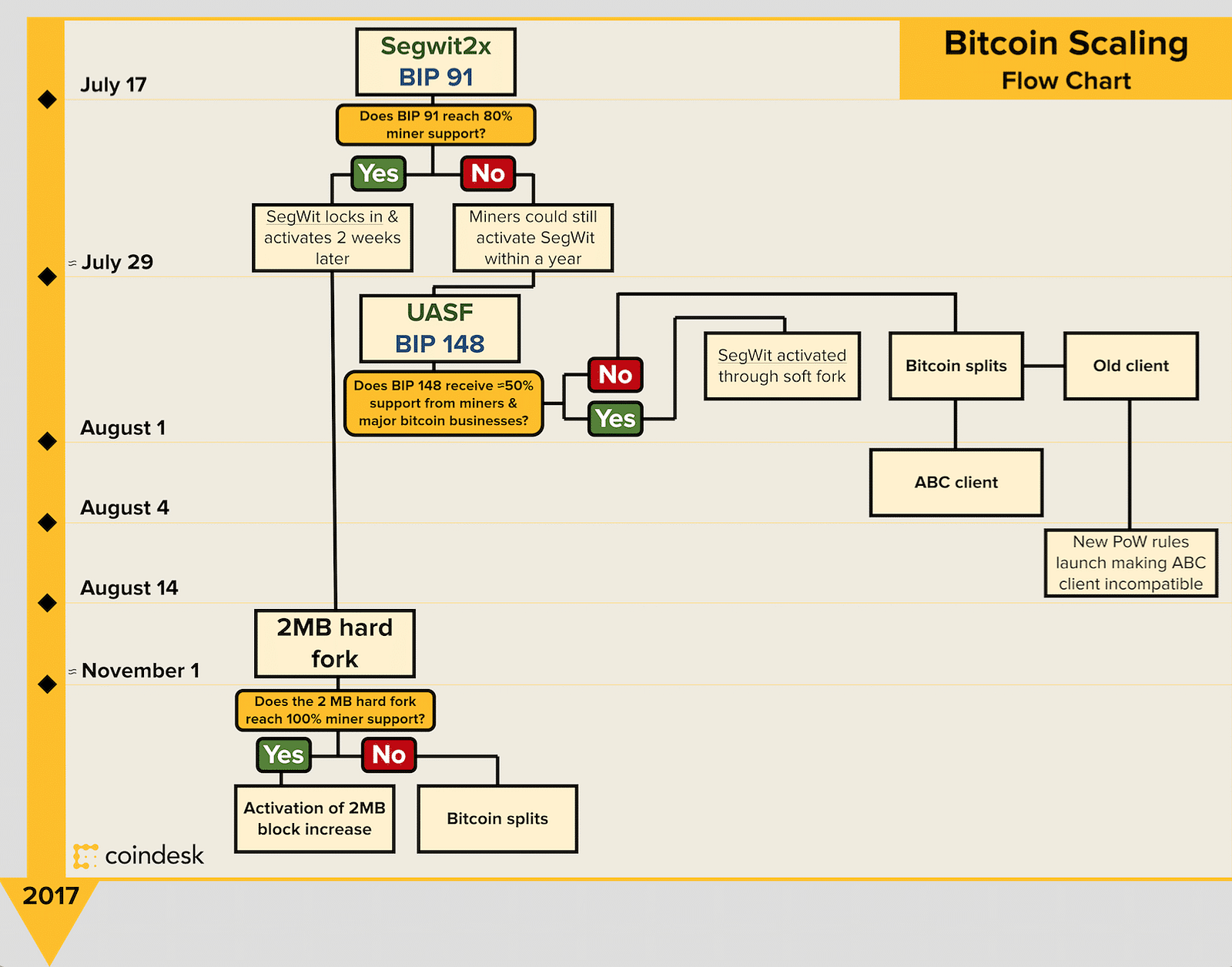

The year 2017 can be considered as the year of forks which aim at increasing the throughput of Bitcoin Blockchain network in a sustainable way. The approach followed by these forks is to increase the block size so that more transactions can be included in each block, thus increasing the throughput.

Let’s look at basics of economics to explain the nuisance behind the block size.

Law of Demand and Supply

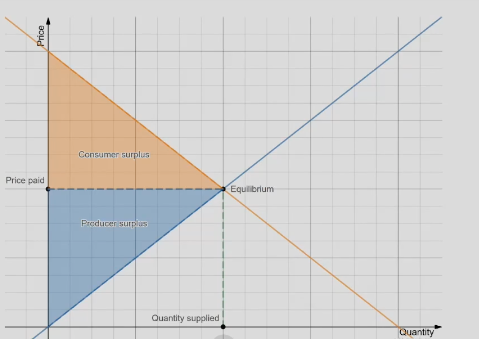

Figure 2 shows the basic supply-demand graph. On the vertical axis is the price of a product per unit and on the horizontal axis is the quantity per period. The blue and orange lines simultaneously show supply and demand. The point of intersection of these two lines gives the equilibrium point.

The orange shaded region in the graph is consumer surplus which is derived whenever the price paid by the consumer is actually less than what the consumer was willing to pay.

The blue shaded region in the graph is producer surplus which is the additional private benefit to producers, in term of profit, gained when the price they receive in the market is more than the minimum price they would be prepared to sell for.

The Bitcoin Market

Bitcoin ecosystem has two types of markets in play:

1. Bitcoin as a currency/commodity, where people trade bitcoins for various personal requirements.

2. Transactional confirmation from Miners: Participants of Bitcoin Blockchain pay miners a fee to validate their transactions and add them to blockchain.

These two markets are complimentary in nature as the exchange of Bitcoin in market 1 is complemented by validation of those transactions in market 2.

We have a quota in market 2 in the form of block size limit of 1 MB. Although it can be argued that market 1 does have a quota (the theoretical limit of 21 million bitcoins), this limit is not relevant while considering the means by which Bitcoin transactions take place. For example, if party A wants to buy $1 million worth of bitcoin, the only quota in play is whether a party B exists who will sell an equivalent value of bitcoin at a mutually agreeable price, nothing else.

Let’s now take a fresh look at our demand supply graph with respect to market 2.

On the horizontal axis, quantity could be assumed as the number of transactions that can be cleared. On the vertical axis is the miner’s fee in Bitcoins. The orange demand line is the number of transactions that market participants want to clear and blue supply line is hash power supplied by miners to clear the transactions.

The red vertical line denotes the quota of 1 MB block size. Since the inception of bitcoin, the quota line has always been firmly to the right of the equilibrium point. This means there was never enough demand to fill up the blocks so the quota actually didn’t matter economically. But once the quota goes to the left of the equilibrium point (the current scenario), things begin to change. The red area in figure 3 is called the dead weight loss. It represents transactions that would have been valuable to both the miners as well as traders but cannot be executed because of the block size quota. This is the economical value which is lost forever.

Also, we see a difference between the producer price and consumer price when the quota is applicable. So consumers - in this case the bitcoin traders - end up paying more than what it takes to validate their transactions. This cost to consumers is not necessarily monetary, but the time they spend waiting for their transactions to be validated.

Is there an urgent need to increase block size?

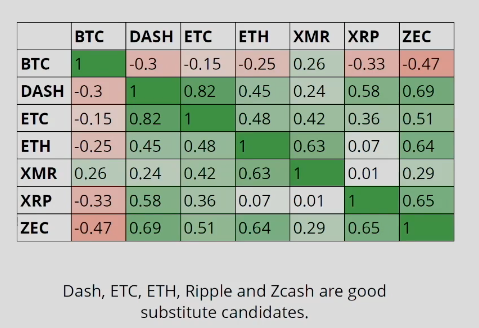

Let’s look at the substitute goods for Bitcoin available in the market. I looked at the correlation of price moment between bitcoin and the other cryptocurrencies in Figure 4 below, and observed a negative correlation between bitcoin and most of the other cryptocurrencies. This means that these cryptocurrencies are a substitute for Bitcoin.

Monero (XMR) is anomalous in that it has a positive correlation with Bitcoin. This could be because these two crypto currencies are tapping different markets with different use cases.

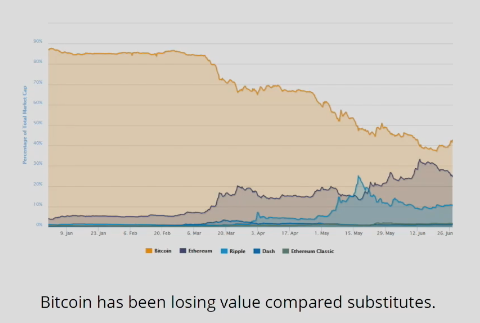

Figure 5 shows a very clear trend of people moving to alternate currencies. This makes a strong case in favour of the quota line moving to the left of the equilibrium point sometime after March 2017, thus making the transactions costly and confirming an urgent need to extend the quota limit.

What Now?

Increasing the block size to a limit that quota line moves to the right of equilibrium point would remove the inefficiencies created due to dead weight loss (Figure 3), thus decreasing the time to verify the transactions.

However, this will decrease the miner’s fees per transaction. To keep the profitability same as earlier, the miner has to increase the number of cleared transactions. This will require the miner to upgrade the hardware required for validating transactions thus making the mining activity profitable for only those players who could afford economies of scale.

This will make the mining activity highly centralized defeating the purpose of a decentralised community driven currency.

Having a constant block size could be a short nearsighted approach to this problem. If Bitcoin takes shape as a dominant international currency, the new block limit will reach sooner or later. A variable block size makes more sense to approach this problem.

Forks are good for a technology as it gives a way to test different approach for a problem. We might see more forks in Bitcoin Blockchain in coming future. Making Bitcoin a scalable and decentralized incentive driven ecosystem is still an ongoing research topic. There are already different communities which are working towards a sustainable approach for the block size problem.

I will be discussing in detail about these implementations in my next post.

Comments ()